“For this program, you needed to shoot for the moon, but settle for much less.”

This comment, casually mentioned at one of our final group meetings, struck a chord with me. Since when does civic engagement involve settling? Do you decide to commit to service work, but feel satisfied when a job is only partly finished? Is it ever fair to pull out of a project or community when your work is by no means done? It’s obviously a reality that you can’t fix everything, especially not in two months. But, if you accept that as fact and don’t work as hard as you can to overcome this limitation, then you are failing. You are failing the community you’ve decided to help, because really, all you’ve decided to do is mess with their lives for a little while and then leave before you need to deal with the repercussions.

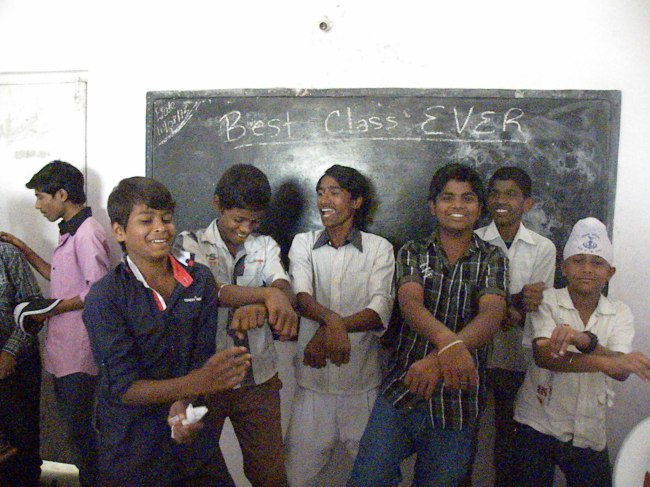

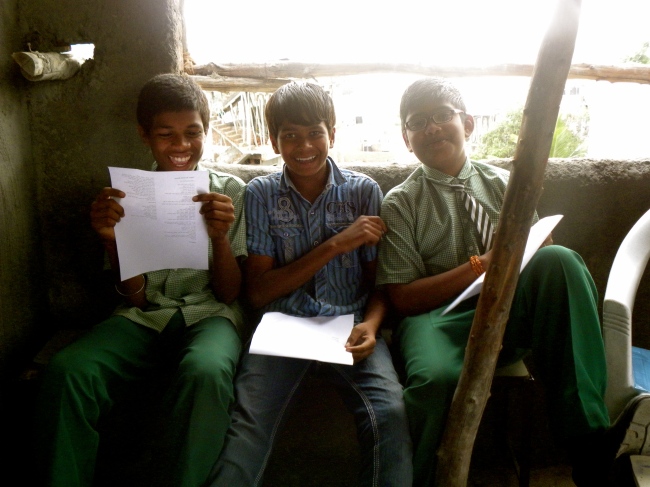

Our final days at Nachiketa Tapovan and Vivekananda Grammar School were filled with smiles and tears and acknowledgement of improvement and gifts from students and teachers alike. Emails and phone numbers were exchanged, with promises to keep in touch and perhaps to start an English club. In those final days, we realized the connections we had made and the relationships we had built up, without noticing along the way. And, even if it doesn’t work out in the long run, we have made an effort to create sustainability in these projects by continuing to communicate with our students through letters and emails.

But our last days at the Aksharavani community were filled with anger and frustration on both sides. Last weekend, we held a sale of donated clothing, toiletries, and school supplies in the community at discounted prices. The profits were to go to painting the bridge school in the community–in other words, the sale was for the community’s benefit, not our own. Yet, somehow, that message was never communicated to the community itself, so the day ended with one vocal community member shouting her frustration that all we did was play with kids and exploit them for money. When we discussed this issue later, some members of our group treated the woman as though her concerns were ridiculous: we were there for them, and even if they weren’t getting a direct benefit, we’re there to show their children love. Who wouldn’t want that? But community engagement is not about telling a community what it needs–it is about asking what it needs, learning about its needs and the assets it already has to meet these needs. It is about working with a community, not for–and this involves communication. You can’t half-ass it, or act as though the community just wouldn’t understand anyway, or claim that the community doesn’t know what’s best for itself. You can’t just show up and do something without explaining motives and leaving room for comments and concerns and suggestions. You wouldn’t want someone coming into your community and walking your kids away without your permission. Your socioeconomic status should not define the amount of respect you receive–respect should be an equal right for all.

I don’t know if our experience with the Aksharavani community was colored by cultural issues, or if the problems I noticed were unique to our project for other reasons. And I’ve only been home for about 24 hours at this point: it will be quite a while before I have processed this trip and made connections between what I learned and what I actually did. But, I guess the most obvious takeaway I have is that the caste system is still prominent in India, no matter what the constitution says. The language used to describe those of lower social status is jarring to hear, after being so used to the PC language of the US; there is little attempt to find commonalities, or form connections with other social classes, even in the realm of civic engagement. And, if anyone who’s reading this happens to have objections, that’s completely fine: I could very well be wrong. India has a population of 1.2 billion people–given the small segment of the population I interacted with, and my own inherent biases as a white girl from California, I can’t make vast judgments about Indian culture.

Now it’s home for 11 days. Let’s hope I can get this processing out of the way before I embark on yet another cultural transformation.