I’ve mentioned before that Chile really enjoys its right to assemble. Protests happen constantly—just before I arrived, a postal service strike prevented mail delivery for weeks, I still haven’t been able to get my student ID because of a strike at the national registry, police have had to use tear gas and water cannons multiple times at protests since I first arrived…it’s just something I’m not used to. It’s especially strange comparing my experience as a student to the radical teens here, who seem to have complete faith that, by continuing to rise up against a government that has given them close to nothing for the past twenty years, they will achieve their dream of a quality, free education for all. This morning, we met with a group of high school students from the Liceo Cervantes, a public school known for its “tomas,” or school takeovers. Essentially, when the students decide that their situation needs to change, immediately, they take a vote and, if the majority agrees, invade the school, placing their list of demands in the windows of classrooms. It’s kind of like when Recess was turned into a movie—no teachers, no classes, no textbooks, just sitting in the school waiting for their needs to be met. And these tomas don’t just last for one or two days. Last year, the students protested from June until August (and are now paying for the missed class time with Saturday classes and one month less of summer vacation). Their demands? Teachers who showed up to class (they didn’t do that) and safe facilities. Apparently, the roof was so old that it was literally falling in on top of students, and yet the administration did nothing—until the students took more drastic measures.

This concept of la toma astounds me. I can’t even imagine what it would be like to not go to school for two months—to instead sleep in a classroom with my peers, play sports in an unsupervised gym, have incredibly mature conversations about equality and respect and autonomy and human rights. I think the most activist thing I did in high school was stand on the corner of Ocean Ave. and Highway 1 holding a sign protesting Prop 8—for all of thirty minutes. I also didn’t have to worry about the roof caving in during AP Lit, but even so, these are things that we just can’t fathom occurring on a fairly regular basis in the United States. So…why? Is it because we’re apathetic? Perhaps. Americans certainly love to live in ignorant, comfortable bliss if they have they opportunity to do so. Protests exist—Moral Mondays, Occupy—just not on this scale.

Or is it because we have faith in the democratic system as a whole, such that we’re willing to wait til the next election to see if things will improve? I personally tend to think this is more accurate. Yes, Americans lack faith in Congress to get anything done anymore (and rightly so—when the nation’s budget is hanging in the balance, we don’t really have time to discuss Green Eggs and Ham). So have we taken over D.C. en masse, picketing Congress until it gets its act together? No. We complain and move on with our lives. I’m sure that some U.S. public schools have leaking roofs and barely legible textbooks. We deal with school segregation and lack of equality in education, and could easily demand a more economically accessible university system, like Chileans do. But we don’t. And I can’t decide if it’s a good thing or not. Yes, our society is a little less chaotic. We learn to be good citizens, creating social change via orderly, governmental channels (and, yes, I’m generalizing a lot right now, but you get my point). We follow the Constitution because we believe that it works—and it does. It’s just that change is slow (as the Founders desired), and so we wait, more or less patiently. It’s just…how long are we going to wait?

I asked the students today why they still have hope that their protests will have success. These student movements have been taking place since 2001, with very little real change. One boy, who I’m sure will someday be a leftist candidate for the Chilean presidency, responded immediately that of course the protests would work, because “we are the future.” “Si la juventud no se mueve, el país no va a crecer.” This is their only method of ensuring change, and so they will use it. I still don’t really understand, but I’m glad that someone has hope.

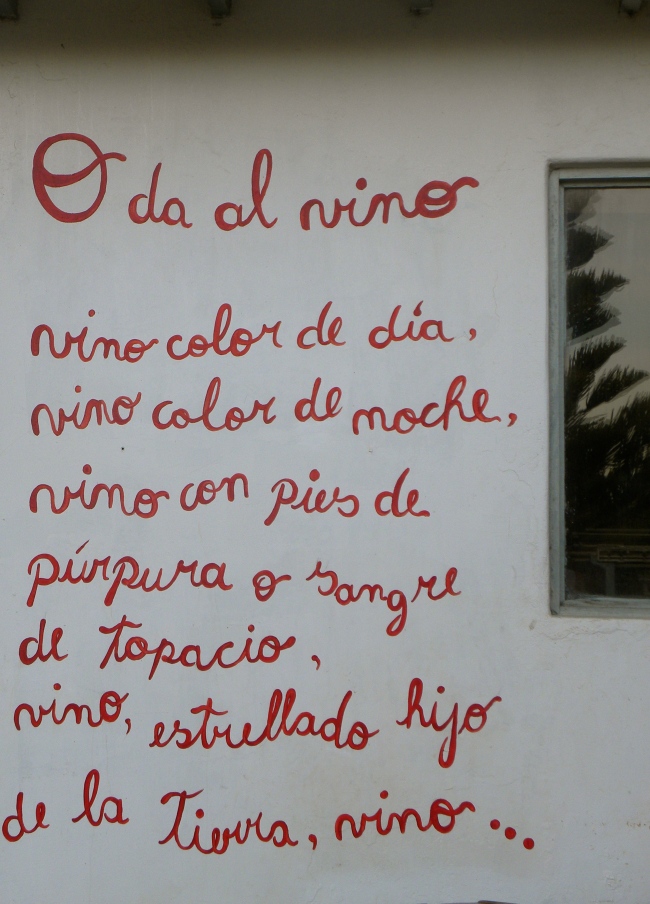

Last week was las Fiestas de Patrias, which is essentially a week of partying for Chilean Independence Day on September 18th (they put 4th of July to shame–hot dogs have nothing on these asados, where you start out with chorizo and end with the biggest rare stake you’ve ever seen). I expected the city to be insane, but it turns out that everyone who can leaves Santiago to go to the beach or the South. Thus, I spent a very calm few days, enjoying asados in San Antonio, personal tours of Pablo Neruda’s home in Bellavista, my first Chilean Starbucks, and the best ice cream in the world (like, really though, voted to be one of the top 25 on Earth, and I was not disappointed). I spent my final day of “rest” climbing into the Andes, scrambling up rocks, past cacti and patches of fresh snow as condors soared overhead, until we finally had panoramic views of the mountains and the entire metropolitan region. I feel like that description was really frilly, but it is so difficult to explain how picturesque it was when we reached the top—not even photos can do it justice.

Kite flying at the beach on Independence Day.

When I say the best ice cream, though, I mean the best ice cream.

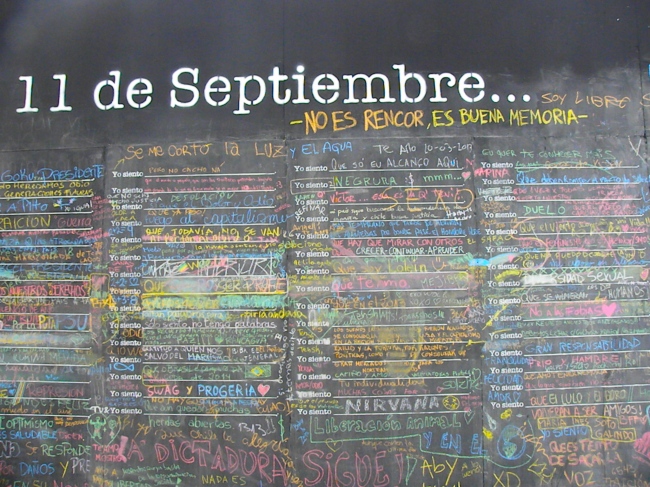

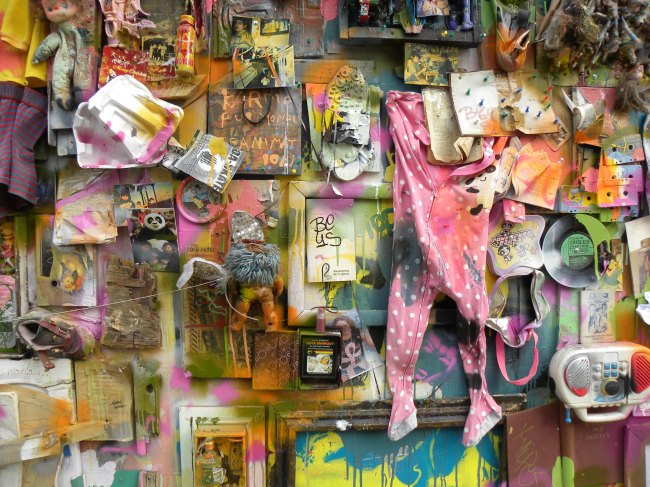

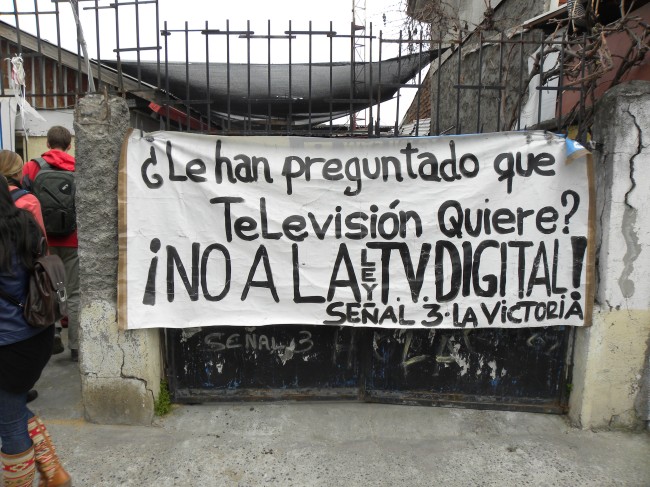

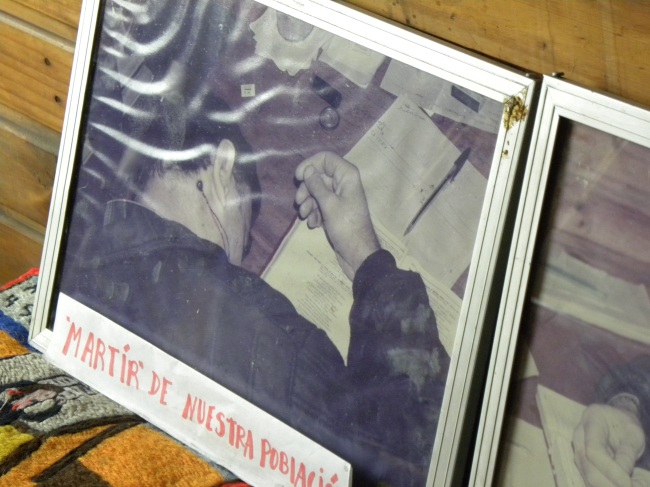

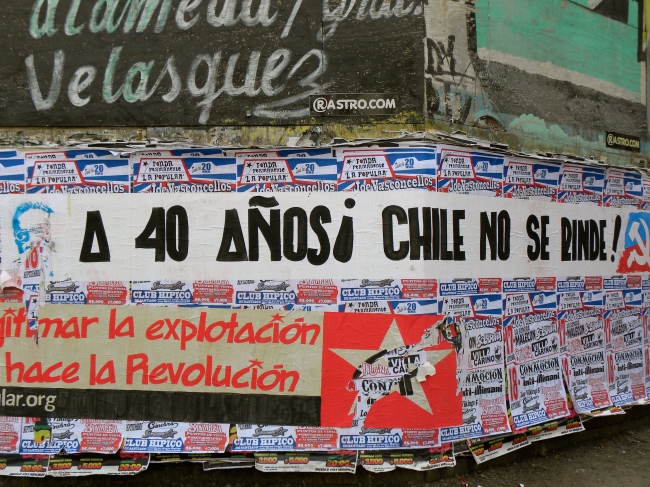

Street art in Bellavista.